As human knowledge through science matures, humans are discovering both the interconnection and interdependence of our external and internal ecology. Validating the poetic and rhythmic medicine of our ancestors.

For thousands of years, we secured our survival on this planet by respecting and observing our environment. Even recognizing an invisible life force in everything around us, which we now know are microbes.

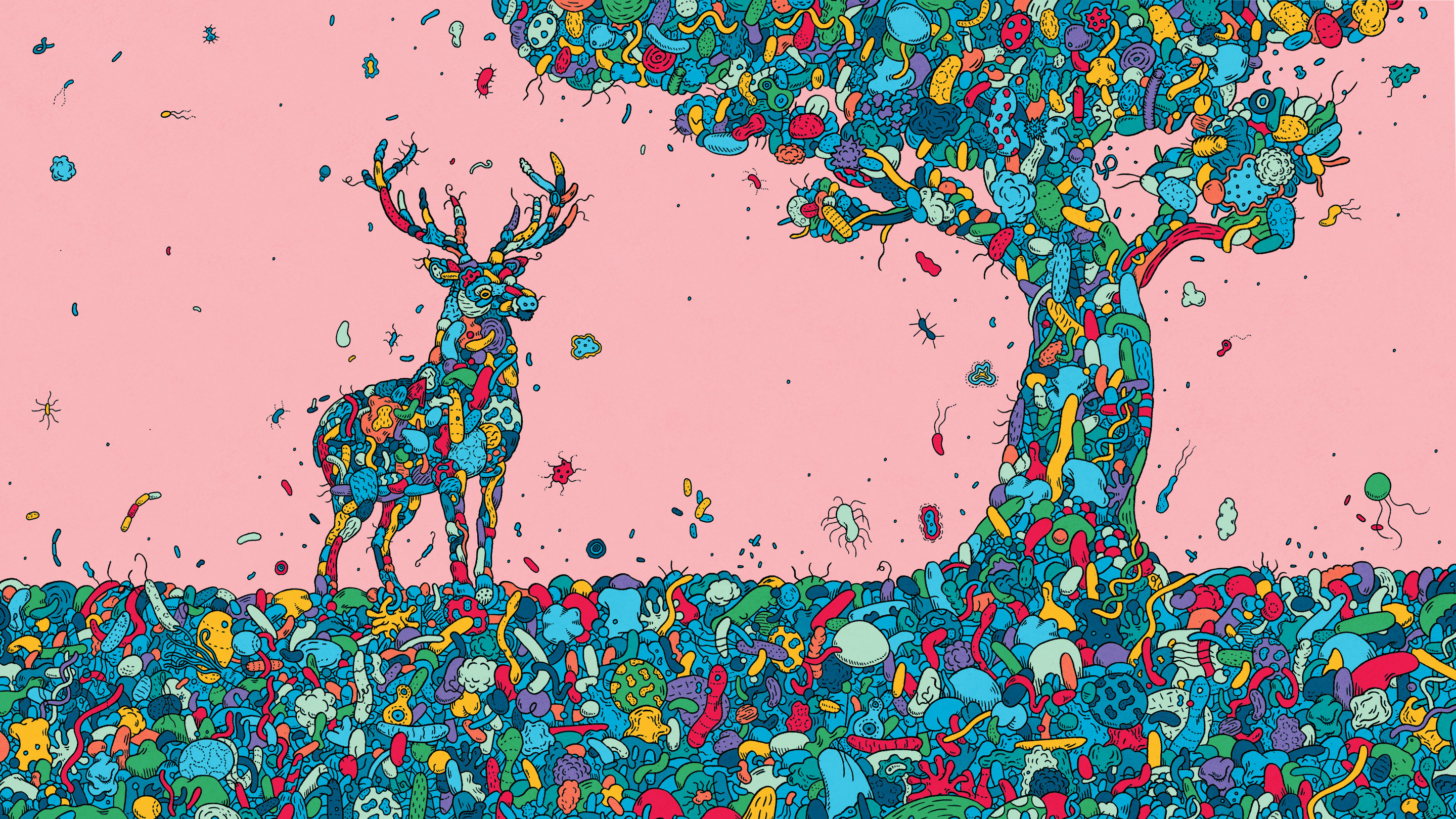

Our human bodies are connected and dependent on the Earth’s body, namely soil and water, but also plant life and other animals.

Both the human body and the Earth’s body are simply hosts for the invisible life comprised of microbes.

Humans caretake the microbiome, in and on their bodies, of which our health and survival is dependent on. The same way our soil’s life is interdependent on the health of the rhizosphere.

Considering that all life on land is dependent on the soil, we can conclude that the health of our soil and the microbes within it, is therefore the most crucial link to our survival on this planet.

What is the Rhizosphere?

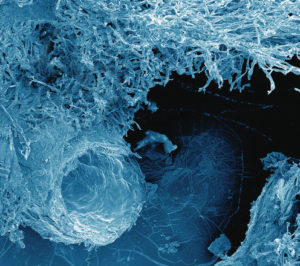

One can look at the rhizosphere as a symbiotic ecosystem which only thrives within a narrow region of the soil. This substrate of soil, on the top layer of Earth, is also called the “root microbiome.”

The complexity of the microorganisms in the rhizosphere are as influential (if not more) to plant growth as are above ground pollinators.

The roots of plants have a fascinating relationship with this microbiome, where the plant communicates with the microbes, and the microbes communicate with each other using quorum sensing.

Root exudates act as signals for microbial recognition, which then draw in the microbes to support plant growth or for disease suppression.

Much of the nutrient cycling and disease suppression needed by plants occurs immediately adjacent to roots due to root Exudates and communities of microorganisms. (1)

Quorum sensing can be simplified as ‘communication’ between that which is invisible to our eyes. The best known examples of quorum sensing come from studies of bacteria, and can occur within a single bacterial species and between diverse species.

Bacteria use quorum sensing to not only coordinate their behavior, but to regulate gene expression in both plants and animals.

Certain bacteria are able to use quorum sensing to regulate bioluminescence, nitrogen fixation and sporulation (2)

Diversity vs. Dysbiosis

With the mistreatment of soil, including ripping up the rhizosphere and the chemical use in conventional agriculture, we have been and continue to disrupt the Earth’s microbiome.

Just as the health of the human microbiome found in our gut, mouth, eyes, skin, and every single organ in our body, can be linked to disease, so can the soil’s microbiome be connected to the health of the planet and atmosphere.

All studies on the human microbiome conclude that a diverse microbiota, with a multitude of species, is shown to be most resistant to disease.

All the Earth’s ecosystems are also dependent on the microbial diversity, signaling growth, defense and survival.

The quorum-sensing function is based on the local density of the bacterial population in the immediate environment. (3)

For multiple generations, our industrialized farming practices have compromised the rhizosphere and have not included any regenerative practices.

By tilling, spraying, and adding chemical fertilizers, we are causing dysbiosis and extinction of vital microbial communities

Our mistreatment of our soil is not only a clear link to our current climate crisis, but also holds the key to the solution we are seeking.

Healthy soil can store more carbon; absorb water like a sponge before becoming saturated, making it more resilient in a dry year; and improve water quality by retaining more water, which reduces runoff from cropland. Healthy soil goes further in meeting the needs of a growing population and food production. (4)

If we want to look at true “root cause” for both human illness and climate change, we don’t need to look further than the soil beneath our feet.

Sustainable is not enough

Back in the late 80’s I studied agro-ecology, also referred to as sustainable agriculture, but now we understand that sustaining the status without regenerating the underlying health, is not enough.

Just as ancestral medicine had always focused on microbiome health, the agricultural practices of our ancestors were leaders in “regenerative agriculture.”

Unfortunately for us, we sacrificed that wisdom and have been treating this land as a commodity, draining the life force from our soil.

But there is hope. We can choose to not only learn from science, but reach back for the wisdom of those who came before us, bridging the brilliance while healing our planet.

My college studies barely skimmed over the true pioneers in regenerative and organic agriculture, including Dr. George Washington Carver who introduced regenerative agriculture to students at Tuskegee University and to southern farmers in the early 1900’s.

Also, Dr. Booker T. Whatley, another professor at Tuskegee, created the first community supported agriculture program (CSA).

It has become clear that those who were stolen from Africa to work in the fields, were intentional targeted from regions with the most advanced and abundant farming practices.

When I later studied with a farmer who celebrated her African heritage, she taught me the importance of dancing and singing while planting seeds in the garden.

Now studies prove how both music and movement stimulates microbial communication and quorum sensing.

Black American farmers and Indigenous farmers have a cultural and spiritual connection to land, and may be willing to teach us how to heal and be true stewards of the soil, before it is too late.

True “Root Cause”

I continue to marvel at how ancient Vedic seers taught microbiome medicine in the musical language of Sanskrit. One example was their focus on the “root.”

Science has now concluded that the diversity of the “root microbiome” in the rhizosphere mirrors the microbial diversity of the human colon.

Interestingly, in Sanskrit the colon is associated with the Muladhara chakra, translated as “root.”

When you look at herbal medicine according to Vedic Science, the plant roots are the most revered for their symbiotic relationship with the human body.

As we know the roots of the plants communicate with the microbes in the soil through exudates, as well as contain phytonutrients that communicate and nourish microbes in our gut.

The Dirt on Climate Change

As I insinuated above, soil ecology is crucial to our survival, and by treating it as a living microbiome we can actually support life on the planet AND slow down the climate crisis.

We know that healthy soil acts alive and dynamic, and that nutrients cannot move on their own or be assimilated without the microbes doing the work.

I have become a broken record by repeating hundreds of times to my clients, that our diet only matters to our microbes.

For it is the microbes that convert the nutrients into our cells. We need to think about how we can feed our microbes.

This holds also true to the soil. The microbes are also responsible for metabolizing, detoxifying, and alchemizing toxins and chemical compounds. Our human genes are not only outnumbered, but feeble in comparison to the evolution and adaptability of the microbial genome.

Increasing demands for food by a growing human population, along with agricultural challenges posed by climate change, are risks to global food security. Microbes in the rhizosphere are involved in many processes that determine agricultural soil productivity, including preservation of soil structure, nutrient recycling, disease control and degradation of pollutants. (5)

We are finally understanding what it means to “feed the soil” and many soil scientists are utilizing microbes, especially fungus, and other prebiotics/probiotics to regenerate the soil’s rhizosphere. And even better, others are adopting the ancestral ways of symbiotic land stewardship.

Clearly, we are never alone. We consume, embrace, inhale, and excrete multitudes of these invisible symbiotic creatures, which are dependent on our care as much as we are dependent on them.

Our enlightened ancestors recognized this invisible life force, and cared for it as a loved one.

In less than 500 years our relationship with the rhizosphere has moved from symbiosis to dysbiosis, and if we do not revert back to caring for our microbes our fate as species in uncertain.

- https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detailfull/soils/health/biology/?cid=nrcs142p2_053868

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1517/13543770903222293?journalCode=ietp20

- https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.165

- https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2019/08/23/soil-health-can-combat-climate-change-from-the-ground-up#:~:text=One%20solution%20to%20combating%20the%20changing%20climate%20starts%20in%20the%20ground.&text=Healthy%20soil%20can%20store%20more,which%20reduces%20runoff%20from%20cropland.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4819777/

Read Previous Post

Read Previous Post