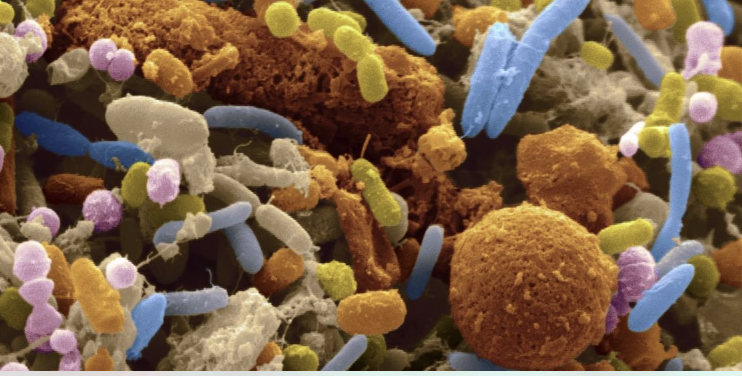

There has been plenty of research about the microbiome and vaginal birth. No doubt, if you just google it and you will be flooded with NCBI reports and other studies.

That being said, I am happy to share some of the fascinating highlights of microbiome transfer via vaginal birth, before we talk about lesser known information of how microbes move from mother to baby in utero.

Some cool highlights

We know that the vaginal flora shifts and expands in the final trimester of pregnancy, to mirror the microbes in the colon, and therefore transfer the microbial fingerprint to the offspring during vaginal birth.

This means that the mothers colon microbiome is identical to her vaginal microbiome, plus more lactobacillus, towards the end of her pregnancy.

We have found that when the “water” breaks, (meaning a rupture in the fluid-filled membranous amniotic sac that encapsulates the baby), then the vaginal microbes flood everywhere including into the baby’s mouth. Baby’s born “in caul” (inside the sac) do not have the same vaginal microbial exposure from a vaginal birth.

A study preformed at Stanford by scientist, Dr. David A. Relman, found microbial DNA in amniotic fluid, apparently from the mother’s mouth, intestines and vagina. Are these the microbes that babies swim in while in utero, and is this why are they covered in vernix?

Wrapped in Vernix

The role of vernix was curious. How did babies come wrapped in vernix, a waxy substance that most likely helps keep certain bacteria from “latching on”?

This vernix is not attained from the vaginal microbiome.

Science concluded this because we knew babies are not “hanging out” for very long in the vagina, plus studies showed that vernix is produced in utero by the sebaceous glands around the 20th week of gestation.

Vernix is theorized to serve several purposes, besides protecting the delicate newborn skin from environmental stress, vernix is also thought to have an antibacterial effect to protect the baby from microbial infections.

Simply the presence of Vernix proved that the uterus in not a sterile environment, as theorized before.

Vernix is comprised of BCFA (branch-chain fatty acids) produced by bacteria, and its existence was discovered throughout the infant gastro-intestinal tract, possibly preparing and safeguarding the newborn GI tract against water-borne bacteria.

Researchers began wonder how babies acquired this protective intestinal bacteria before birth, so they turned to the placenta.

Hundreds of studies have looked at bacteria that inhabit the mouth, skin, vagina and intestines, but the placenta was unexplored territory.

Referred to as the baby’s twin, this incredible organ that forms inside the uterus, providing “life support” for the fetus, including transport of oxygen and nutrients, removal of wastes, secretion of hormones, and now possibly an intrinsic source of the human microbiome

“People are intrigued by the role of the placenta,” said Dr. Aagaard, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston. “There’s no other time in life that we acquire a totally new organ. And then we get rid of it.”

Baby’s Twin, the Placenta

In 2014, a study led by Dr. Kjersti Aagaard, discovered that the placenta had 300 different types of bacteria, most of them commensal and harmless.

Dr. Aagaard and her team became curious about the placenta when they noticed something puzzling in earlier research on the vaginal microbiome in pregnant women.

The scientific assumption was that the bacterial profiles of the mother’s vaginal microbiome would be similar to that of the babies intestines, particularly in babies born vaginally, however these microbes did not match.

Previously the placenta was thought to be sterile and void of microbes, but by using a DNA sequencing technique called metagenomics, scientists discovered that the placenta actually harbors a world of bacteria.

The team compared these microbes to those previously found in other parts of the body, including the mouth, skin, nose, vagina and gut.

The closest match, by far, was between the placenta and the mouth, which also resembled babies’ intestinal microbiome in the first week of life.

These placental bacteria are different from that found in the vaginal microbiome, and what is super fascinating is that this placental microbiome is most akin to the human oral microbiome.

This unique placental microbiome is primarily composed of nonpathogenic commensal microbiota from the Firmicutes, Tenericutes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Fusobacteria phyla. (more on this later….)

This finding suggests that babies may acquire an important part of their normal gut bacteria from the placenta, although the placenta was less than 10 percent bacteria by mass, compared to the large intestine that is 90 percent bacteria.

From the Mouth of Mothers

For years, scientists have theorized that the mother’s oral bacteria travel through her bloodstream to the placenta, take up residence there and find their way into the fetus.

Animal studies supports this theory, when oral bacteria injected into a vein in pregnant mice, this bacteria populated the placenta.

What this means is that the placenta mirrors the vast and diverse microbiome of the mother’s mouth. Therefore verifying that any substance a pregnant woman puts in her mouth during pregnancy, is transferred to the placenta.

The idea also confirms what many birth professionals have noted for years, women with periodontal disease have a higher risk of having premature or low-birth-weight babies.

Recommendation of treating oral health of pregnant women has had positive implications in the health of her baby.

This also confirms why studies show a dysbiotic mix of bacteria in the placentas of premature babies.

From Tip to Tail

If we look at the human body as simply a host, created to house an invisible entity, which systematically controls how we think, how we feel and how we heal.

This invisible entity, named the microbiome, must keep the host alive and healthy in order to survive. Therefore, strategically creating communities in different areas of the host to ensure survival.

In order to fully understand the brilliance of this strategy, we can take a stroll down the digestive tract and observe where these communities reside.

When we look at the human digestive tract, there are trillions of microbes in the mouth, with less and less communities as it moves down the digestive tract, until we reach the large intestine and colon, where it explodes in population once again.

If you look at the upper part of the small intestine, where it meets the stomach, this is actually a vapid environment for microbes and it isn’t until the ileocecal valve, where it meets with the large intestine, that the jungle of microbes flourish again.

The microbes in the mouth (the tip) start the process of nutrient extraction and immune function and then the microbes in the tail of the digestive tract complete the rest of the metabolic. anabolic, and catabolic processes.

Colon-izing the Host

The microbiota needs to inoculate the host at the beginning of life, and each community plays an important role in human survival.

Since babies are born from our “tail”, that community will clearly have an advantage to inoculate the host.

It is even theorized that humans are typically born head down, facing posterior, to have an additional opportunity to be exposed to the mother’s fecal matter.

Now this may gross you out, but majority of mammals from mice to gorillas have participated in coprophagy for reasons unknown to us.

So, for the human microbiome to successfully complete the diverse colonization needed for survival, it would be essential for the microbial community of the mothers mouth to have a bit of a head start before this newly born “host” is thrust into the world.

In theory, the baby is later exposed to the additional microbes of mother’s mouth through kisses and sharing food when baby’s digestive tract is ready.

I am certain it is not a coincidence that the human baby develops teeth much later after birth, and traditionally needed food “pre-chewed” by the mother’s mouth, as their first exposure to solids after nursing.

Unique Microbial Colonies

The mother’s vaginal microbiome is different from the all other colonies in the body, with the largest population of Bifido lactobacillus.

This exposure at birth helps support the essential Bifido strains crucial for the baby’s immune system. (you can learn more about this amazing dynamic here).

The microbes found in the mother’s mouth and baby’s placenta are strains that are more prominent in developed digestive tract in an adult, especially Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes.

These microbes will eventually outnumber Bifido as we grow, wean from mother’s milk and eat food.

But just like any system, these microbes depend on each other to create a healthy dynamic structure and complete their unique jobs.

The Bifido strains are responsible for growing the baby’s brain and immune system, while Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes are responsible for establishing a healthy digestive tract.

Only Time Will Tell

The result of these studies are bringing us closer to understanding how our microbiome protects us, the human host, from inception through birth and beyond.

How we will use this information to support women and babies during pregnancy and in labor, is unclear.

In the words of Dr. Martin Blaser from the American Microbiome Institute; “Pregnant women are often given antibiotics, for all kinds of reasons, many justified, but there’s a slippery slope. What are the antibiotics doing?”

Now that we know that the placenta is not sterile, that it mirrors the microbiome of the mother’s mouth, and has an essential role for seeding the baby’s microbiome, “will this be a productive lead,” questions Dr. Blaser, “or will it fizzle out? Time will tell us.”

Read Previous Post

Read Previous Post